In Brief

On 4 December 2024, the Commissioner released the following new draft guidance materials (Draft Guidance) on Australia’s new thin capitalisation regime:

- TR 2024/D3 Income tax: aspects of the third-party debt test in Subdivision 820-EAB of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (TR 2024/D3)[1] and

- Schedules 3 and 4 to PCG 2024/D3: Restructures and the thin capitalisation and debt deduction creation rules – ATO compliance approach (PCG 2024/D3).[2]

Australia’s new thin capitalisation regime was enacted in April 2024 and generally applies for income years commencing on or after 1 July 2023.

The Draft Guidance informs taxpayers of the Commissioner’s proposed approach to interpreting and administering the third-party debt test (TPDT) — a unique new test designed to “[operate] effectively as a credit assessment test, in which an independent commercial lender determines the level and structure of debt finance it is prepared to provide an entity.”[3]

Despite some key positives, the Commissioner generally takes a very restrictive view of the TPDT, to a point where the test may be inaccessible and unworkable for many of those taxpayers at whom it is directed.

The Draft Guidance is open for comment until 7 February 2025. Alvarez & Marsal will be making a submission.

In this context, we summarise the broad purposes, as well as some key positives and negatives, gleaned from the Draft Guidance.

High-level refresher: What is the TPDT?

In very broad terms, the TPDT is a new, optional thin capitalisation test, introduced alongside the new fixed ratio test (FRT) and group ratio test (GRT). The Explanatory Memorandum to the enacting legislation[4] expressly states that the TPDT is intended to provide an alternative to the FRT and GRT for asset heavy sectors with long depreciation periods, such as the infrastructure and property sectors.[5]

The TPDT limits an entity’s debt deductions to those deductions that are “attributable” to “debt interests” that satisfy each of the TPDT conditions. If a taxpayer’s arrangements satisfy the TPDT conditions, it may permit a greater (maximum) quantum of debt deductions compared to the other tests.

The TPDT is supplemented by “conduit financing conditions.” Broadly, these additional conditions allow taxpayers to “on-lend” within a corporate group (on back-to-back terms) and still access the (potentially, larger) TPDT limit on debt deductions, as compared to the FRT and GRT.

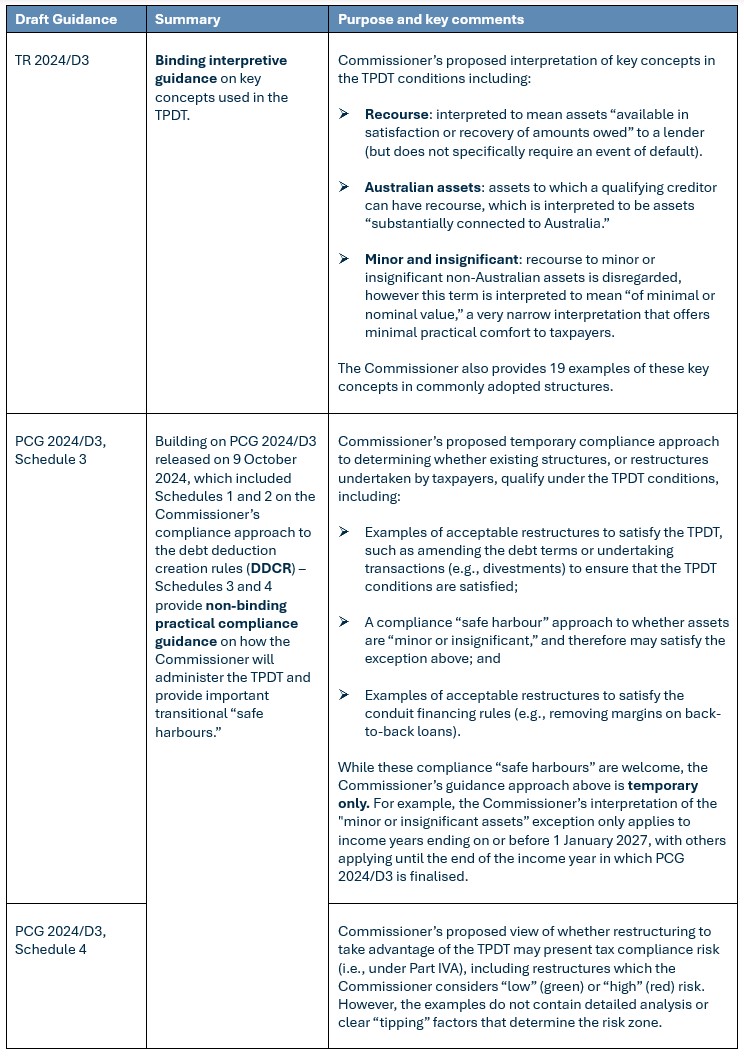

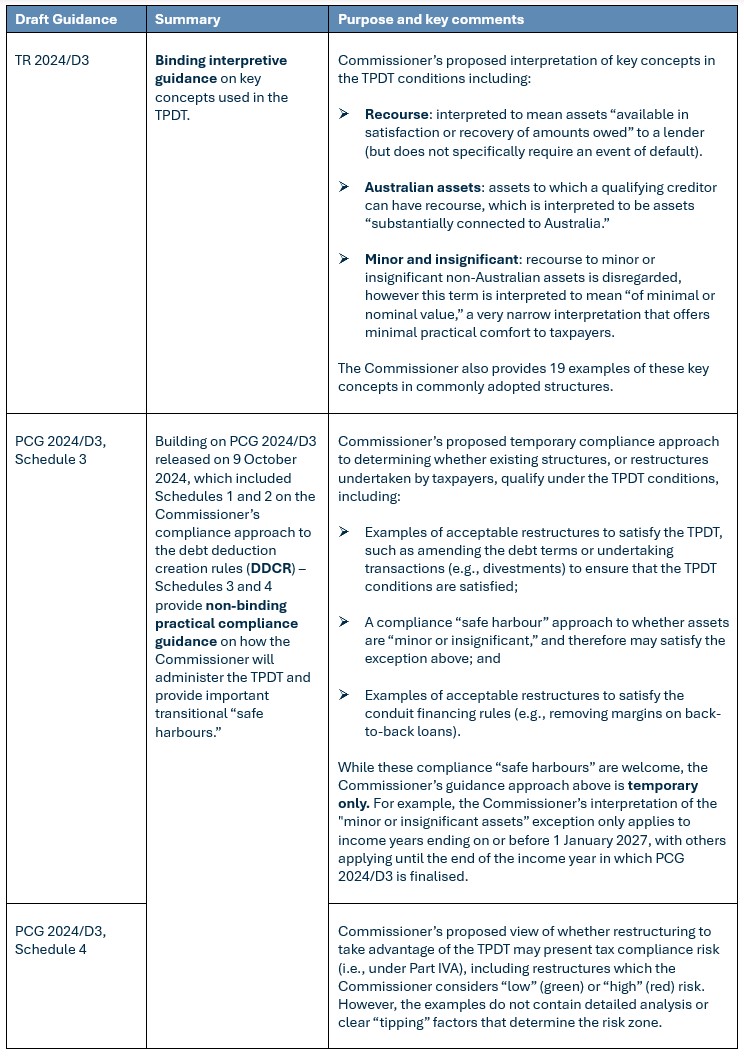

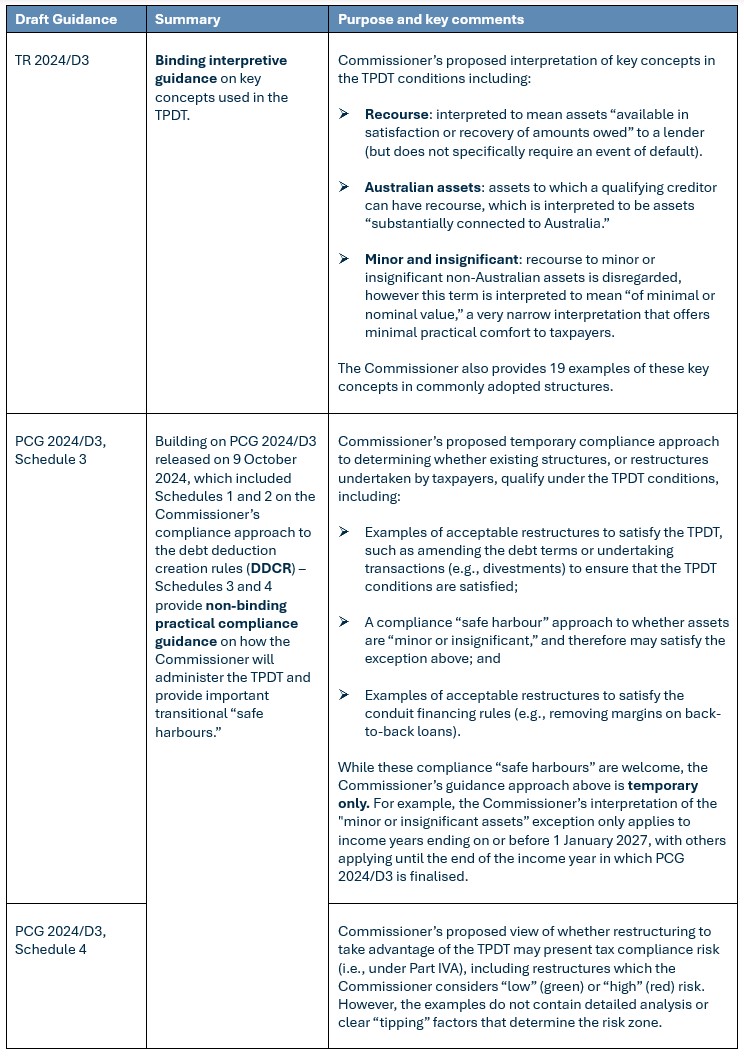

What did the Commissioner release, specifically?

The table below provides a broad summary of the contents and stated purposes of the new Draft Guidance.

The roses: Helpful updates on the TPDT from the Draft Guidance

The Draft Guidance includes the following important, and positive, developments for taxpayers looking to interpret and apply the TPDT:

- When do you need to test: The Commissioner has provided binding interpretive guidance in TR 2024/D3 on when each of the TPDT conditions need to be tested. Under the legislation, each TPDT condition must be satisfied in respect of a specific “debt interest,” “in relation to” the relevant income year in which debt deductions (interest, borrowing costs, related interest swap costs, etc.) arise.

- Helpfully, the condition in s. 820-427A(3)(a) — that the debt interest is issued to an entity that isn’t an “associate entity” of the borrower — must be satisfied only at the time of issuing the debt interest. This means that should the lender and borrower become associate entities in future years while the debt interest is on issue, this will not of itself mean that the TPDT conditions will be failed for those prior income years.[6]

- What is recourse: The Commissioner’s guidance in TR 2024/D3 states that, when considering whether an entity has “recourse” to Australian assets, it is only necessary to look to “direct” recourse in most situations.

- For example, if an entity borrows from a third-party lender, and the debt is secured against all its assets (e.g., including a trade receivable), the Commissioner’s view is that it is not necessary to “look through” the receivable to the trade creditor’s assets when considering if the lender has recourse only to Australian assets of the borrower.[7]

- However, if taxpayers are considering whether a creditor has recourse to “credit support rights” (e.g., guarantees, letters of credit, or equity commitments), the TPDT conditions in s. 820-427A(5) require consideration of “direct and indirect” recourse. This is considered further below. PCG 2024/D3 also includes a transitional compliance approach allowing taxpayers to remove recourse to foreign assets to comply with the TPDT (for restructures before the end of the income year in which PCG 2024/D3 is finalised).[8]

- Transitional compliance approach on “minor or insignificant” assets exception: As noted above, the Commissioner provides some practical guidance in Schedule 3 to PCG 2024/D3 on what is considered (at least, for a limited time period) to be an acceptable quantum, and proportion, of a borrower’s assets that could be disregarded, when considering whether their creditors have “recourse only to Australian assets.” Relevantly, PCG 2024/D3 considers that for existing arrangements, minor or insignificant assets will include those that are:

- No more than 1 percent of the entity’s total assets (in aggregate);

- Individually are worth no more than $1 million; and

- Are not credit support rights (provided by any entity).

Although welcome, this effective “safe harbour” is narrow and will be difficult to satisfy for many sophisticated borrowing arrangements (which will almost certainly involve credit support rights as collateral). This safe harbour is also temporary only, being limited to income years starting on or after 1 July 2023 and ending on or before 1 January 2027. Further, the binding and permanent interpretative guidance proposed in TR 2024/D3 takes a much narrower view of the “minor or insignificant assets” exception, applying it only to assets of minimal or nominal value (citing an example of a Foreign Sub Co with share capital of $2 and no other assets — see further details on this below).

- Restructures to comply with the conduit financing provision: The Commissioner has provided some helpful examples in PCG 2024/D3 of the proposed transitional compliance approach in relation to restructures that are undertaken to allow a taxpayer to comply with the conduit financing provisions in s. 820-427C(1). This is a welcome approach which provides an avenue for taxpayers to satisfy the TPDT conditions for restructures undertaken before the end of the income year in which PCG 2024/D3 is finalised, and until 1 January 2027 for certain restructures. Examples of where the Commissioner will only apply limited compliance resources to verify the positions taken include:

- Removing a margin on a project finance on-loan to ensure that the terms of the on-loan match the external loan;

- Where there are multiple external loans, the creation of separate on-loans to match each of those external loans; and

- Closing out an on-swap and blending the effect of the on-swap into the on-loan such that new on-loan reflects the terms of the external loans and the external interest rate swap.

The thorns: Unfortunately, there are many.

As an overarching comment, and other than as outlined above, the Draft Guidance takes a very strict view both on how the TPDT conditions should be tested, and whether or not a taxpayer meets them. Disappointingly, the Commissioner has also read-in a degree of policy intent into the interpretation of the TPDT conditions, which is not apparent on the face of the legislation.

Key takeaways for taxpayers looking to apply the TPDT include:

- Binding guidance: TR 2024/D3 would be, when finalised, a binding product — meaning that the Commissioner is bound to interpret the relevant conditions in the same way that it has interpreted them in the ruling itself, when applying the TPDT conditions to any covered taxpayers or arrangements. Accordingly, taxpayers who take reasonable, but opposing, positions when attending to their affairs would have recourse (pun intended) only to the courts when advocating for that view.

- Conditions must be passed for the whole year: Based on the Draft Guidance, several of the TPDT conditions must be satisfied by a debt interest throughout the entire income year for the arrangement to qualify. This means that:

- Other than in respect of the first TPDT condition in s. 820-427A(3)(a), taxpayers must continually test their arrangements, monitor their assets (at least those to which lenders may have recourse), and track the use of their third-party debt funding, throughout every income year — a heavy compliance burden.

- Each condition must be satisfied for the full income year (or the entire time the debt is on issue, if issued partway through the income year).

- Taxpayers cannot restructure, amend or otherwise alter their arrangements in order to satisfy the TPDT conditions during an income year, if they are to satisfy the test for that income year. This seems to contradict the purpose of Schedule 3 to PCG 2024/D3, which allows taxpayers to alter their affairs (in certain circumstances) to satisfy the TPDT.

- Recourse to minor or insignificant assets: Many taxpayers were hoping for clarity in relation to what is “minor or insignificant” in the context of the recourse TPDT condition in s. 820-427A(3)(c). While the Draft Guidance provides a clear view, it is not a concessional one.

- On a permanent basis (i.e., outside of the transitional compliance approach included in Schedule 3 of PCG 2024/D3) the Commissioner’s view is that this exception only covers assets of “minimal or nominal value.” In addition to Example 8 which includes a Foreign Sub Co with share capital of $2 and no other assets, Example 9 confirms the Commissioner’s view that a foreign subsidiary with a market value of $10 million will not be “minor or insignificant” — even where that represents only 2 percent of the Australian multinational group. [9]

- The Commissioner further states that “[the] actual or hypothetical impact of any ineligible assets on the quantum or terms of the debt interest is not determinative of whether those assets are minor or insignificant.”[10] This illustrates the Commissioner’s unreasonable position that where a lender has recourse to any non-Australian assists with more than nominal value, the debt interest will not satisfy the TPDT conditions, even if the non-Australian asset is, relatively speaking and as a practical matter for that taxpayer, a minor or insignificant asset.

- This contrasts with the purpose of the TPDT as identified in the Explanatory Memorandum, i.e., that the test stands in for an “independent commercial lender”[11] — even if such a lender would disregard an asset, this appears not to matter for the Commissioner’s purposes.

- Recourse relates only to Australian assets: Aside from indicating that qualifying assets (to which lenders can have recourse) must have a substantial connection to Australia as is required under s. 820-427A(3)(c), the Draft Guidance does not provide any parameters, or indicia, for taxpayers to determine whether assets (particularly, intangibles) have such a connection.

- For example, while the Draft Guidance indicates that assets (e.g., receivables from any entity) that give rise to Australian assessable income may have a sufficient Australian connection,[12] other key assets that taxpayers must have regard to when considering the recourse conditions include contracts, rights (particularly credit support rights), receivables, intellectual property — all of which may have uncertain “locus” — and the Draft Guidance omits any commentary on how to determine whether they are relevantly Australian.

- The Commissioner provides some insight into whether or not shares that a borrower holds may be an Australian asset. However, without a clear legislative basis or degree of measurement, the Commissioner indicates in Example 13 that shares in an Australian-incorporated (and tax resident) entity would not be Australian assets, on the basis that the entity has an overseas permanent establishment which renders its connection to a foreign jurisdiction “more than tenuous or remote.”[13]

- Indirect recourse: As discussed above, the Commissioner helpfully states in TR 2024/D3 that, when considering “recourse” as a term of itself, s. 820-427A(3)(c) does not require taxpayers to “look-through” assets that are rights. However, s. 820-427A(5) determines whether credit support rights (which are generally prohibited as recourse for lenders under the TPDT) may be subject to an exception — rendering them permissible recourse. That subsection tests whether a lender has recourse “directly or indirectly” to another entity (i.e., an associate entity of the borrower) when testing those conditions. However, the concept of indirect recourse is left uninterpreted by the Commissioner in the Draft Guidance. Presumably, this leaves open the question of whether taxpayers are required to look-through credit support rights to the assets of the credit support provider (or further) in considering the TPDT conditions.

- Requirement to trace the use of third-party debt: In respect of the TPDT condition in s. 820-427A(3)(d) – which broadly requires that all, or substantially all, of the third party debt funding be used to fund “commercial activities in Australia” — the Draft Guidance and in particular TR 2024/D3 takes an incredibly restrictive approach and imports into the law an ongoing tracing requirement that is not evident on the face of the legislation. Specifically, TR 2024/D3 states that this “use” of funds requirement is not a “once off” test, and is a factual inquiry.[14] The brief example provided in TR 2024/D3 indicates that where a taxpayer uses third-party debt to invest in an Australian asset, the taxpayer would need to “reassess how it continues to ‘use’ those proceeds if the Australian asset is disposed of, and the proceeds of the sale are redeployed.”[15] This leaves taxpayers with a heavy evidentiary burden, with no guidance from the Commissioner on how to practically discharge this burden, or how far into the future they must do so.

- The Commissioner’s proposed approach will create a significant compliance burden for taxpayers and administrators (apparent from the Commissioner’s longstanding administrative approach in other contexts, for example s. 45B of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936).

- Further, the Commissioner’s tracing approach here is even less commercially palatable than that in respect of the DDCR in PCG 2024/D3 Schedules 1 and 2, which states that tracing is a factual exercise and that taxpayers should not claim debt deductions unless they have sufficient evidence to demonstrate the use(s) of related party debt and that the DDCR does not apply (and provides limited options in terms of fair and reasonable apportionment or alternatives to tracing).

- Distributions to investors and other capital management transactions are not “commercial activities in connection with Australia”: Unfortunately, TR 2024/D3 goes further in reading into the legislation a policy intent that “the payment of distributions and capital management activities” are not “commercial activities in connection with Australia” for the purposes of the TPDT condition in s. 820-427A(3)(d).[16] The application of this concept to third party borrowing used to fund trust distributions in Example 16 of TR 2024/D3 is troubling, suggesting that “commercial activities in connection with Australia” are limited to the initial operational investment and profit-generating activities themselves (even though the distribution of those profits or other returns to investors is the very object of such “commercial activity.”) The Commissioner’s proposed interpretation of this TPDT condition adds to the onslaught of integrity rules which focus on the funding source of distributions and returns to shareholders and imports into the TPDT a tracing requirement for dividends and other distributions which is not evident in the legislation itself. Practically, the combined impact of recent integrity rules (and the Commissioner’s proposed administration of those rules) means that complex tracing and identification of whether returns to investors are funded with “good” or “bad” funds will be required — and means that tax is significantly limiting the sources from which it might be commercially feasible to fund such distributions. In particular, various new rules prevent:

- Corporate taxpayers from funding franked distributions with the proceeds of equity raisings (due to the equity funded distributions rule in s. 207-159);

- Taxpayers subject to the thin capitalisation rules and relying on the TPDT from funding dividends or other distributions with third party debt (due to the TPDT “use” condition in s. 820-427A(3)(d)); and

- Taxpayers subject to the thin capitalisation rules and relying on the earnings-based tests from funding dividends or other distributions with related party debt (due to the DDCR in s. 820-423A(5)).

Conclusion: A preference against debt?

The Draft Guidance builds on the Commissioner’s longstanding preference for cash and equity funding over debt funding for multinational businesses. This is not surprising given the Commissioner’s recent approach in Schedules 1 and 2 of the PCG 2024/D3 in respect of the DDCR, which clearly reflects this preference (especially as it relates to the use of related-party debt and any refinancing of that debt). However, the approach in the Draft Guidance takes this one step further and places a question mark over the ability of Australian businesses — particularly those in capital intensive sectors with long investment horizons such as the property and infrastructure sectors — to fund their operations (and distributions to investors) with genuine third-party debt. In particular, the Commissioner repeatedly states in the Draft Guidance that the TPDT is intended to be narrow in its application, but the Commissioner’s reading in of policy intent to the interpretation of the TPDT conditions takes this “narrow” test to a point where the TPDT may be inaccessible and unworkable for many of those taxpayers at whom it is directed.

Consistent with the approach taken by the Commissioner in respect of the introduction of other new measures (e.g., hybrid mismatches), we expect taxpayers will be required to make certain disclosures in their international dealings and reportable tax position schedules, particularly where restructures have been undertaken in anticipation of the new rules. In this vein, we expect “debt” to continue to be a key focus of the Commissioner in 2025. Taxpayers are encouraged to actively consider their arrangements in the context of the new thin capitalisation rules and Draft Guidance and prepare accordingly.

As noted above, the Draft Guidance is open for comment until 7 February 2025, and we expect many stakeholders to make submissions on the Commissioner’s proposed approach.

[1] Australia Tax Office, Draft Tax Ruling, “Income tax: aspects of the third party debt test in Subdivision 820-EAB of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997” https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=DTR/TR2024D3/NAT/ATO/00001

[2] Australia Tax Office, Draft Practical Compliance Guideline, “Restructures and the thin capitalisation and debt deduction creation rules – ATO compliance approach,” https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=DPC/PCG2024D3/NAT/ATO/00001

[3] Paragraph 2.90 of the Explanatory Memorandum.

[4]Treasury Laws Amendment (Making Multinationals Pay Their Fair Share—Integrity and Transparency) Bill 2024.

[5] Page 79 (Impact Analysis) of the Explanatory Memorandum.

[6] Paragraphs 30 and 31 of TR 2024/D3.

[7] Paragraph 42 and Example 5 of TR 2024/D3.

[8] Paragraphs 223 to 226 and Examples 20 to 22 of Schedule 3 to PCG 2024/D3.

[9] Example 9 of TR 2024/D3.

[10] Paragraph 64 of TR 2024/D3.

[11] Paragraph 2.90 of the Explanatory Memorandum.

[12] Paragraph 85 of TR 2024/D3.

[13] Paragraph 83 of TR 2024/D3.

[14] Paragraphs 99 and 100 of TR 2024/D3.

[15] Paragraph 99 of TR 2024/D3.

[16] Paragraph 107 of TR 2024/D3.

https://www.alvarezandmarsal.com/insights/australias-new-thin-capitalisation-guidance-some-roses-many-more-thorns